Kit Curry is one of twelve artists selected as a Gallery 263 Small Works Project artist. This project presents artwork in flat files at the gallery and on our website for the duration of one year. All artists are based in Massachusetts.

Can you tell us a little about yourself?

I am an artist and illustrator living in the Berkshires. My wife and I moved here from Brooklyn in 2017, which seems prescient now. It’s a good time to live out in the sticks; a good time to hole up and make art. Or cook, or sing along with my DIY karaoke machine — or in my wife’s case, make books and fiber crafts. It’s a bit like the frame story in the Decameron: we’re out in the country telling each other stories while the plague rages on elsewhere. Given the circumstances, it’s the best life anyone could hope for.

What kind of art do you make?

My work is illustrative and pictorial — windows into quiet little worlds. I grew up around paintings by my great great grandfather, the illustrator Harvey Dunn. The stories those pictures once illustrated were lost to us, so what was left were evocative glimpses of narratives you could never quite get a hold of. I think of my pictures that way: illustrations for an absent story.

I don’t have a lot of formal art training. My grandmother, Diana Rutherford, was an artist who used to work and show in Cambridge — she got me started at a young age. The best of my subsequent instruction has been gotten from old books by artists long dead.

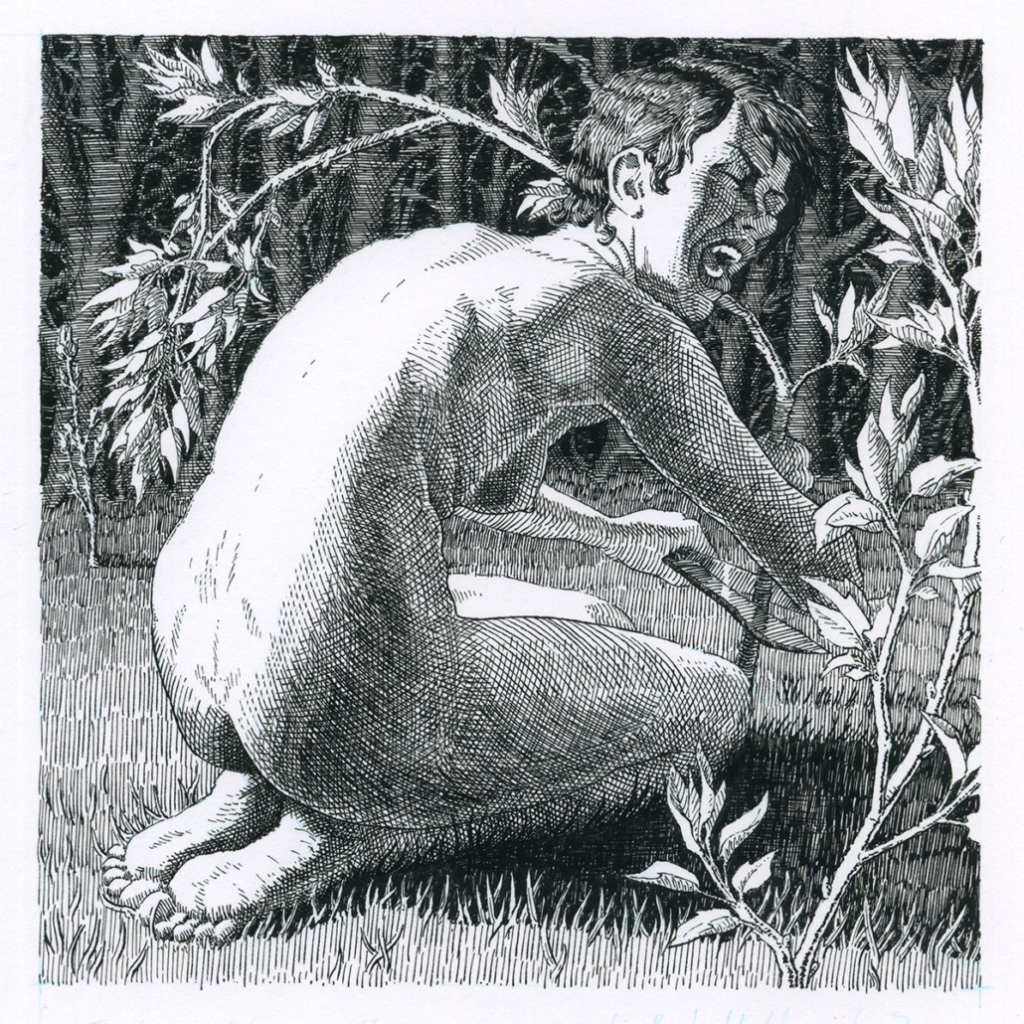

What concepts does your art explore?

Art-making for me is less about self expression than self-forgetting; about stepping into a river of tradition and letting it carry me along; maybe about reaching for something bigger, better, or at least more final and complete than a self. Dunn used to talk about ‘the brotherhood of man.’ Maybe we can update that to ‘the kinship of humanity.’ Universality is a pipe dream, but I do think you need to make that doomed appeal to something beyond yourself.

To that end, the big themes that I work with have very deep roots: death, the unknown and unknowable, and keeping joy alive in bleak times.

So there’s an aspect of communion with ancestors when I make art. Likewise with cooking: my father was a chef. (Locals might remember the Cottonwood Cafe on Mass Ave.)

Can you tell us about the work you have on view in your flat file drawer at the gallery?

images of work

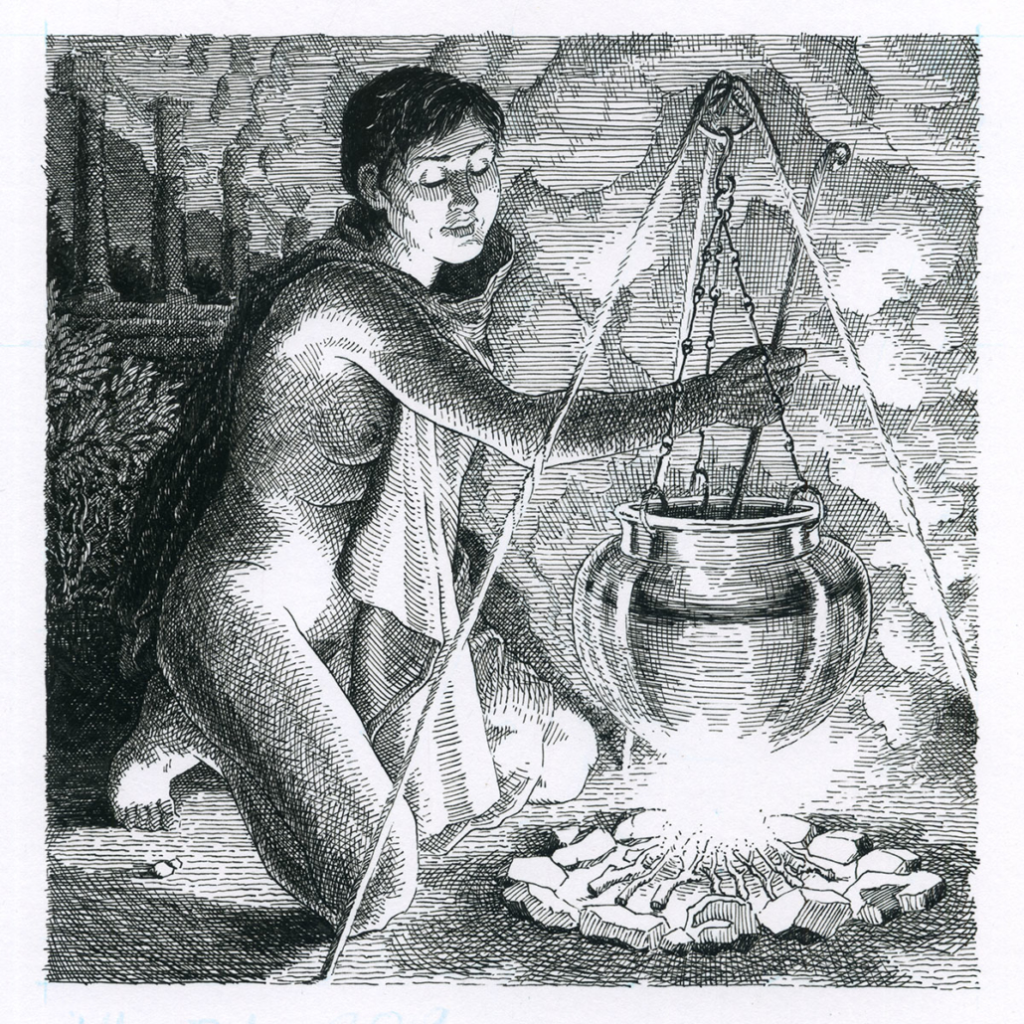

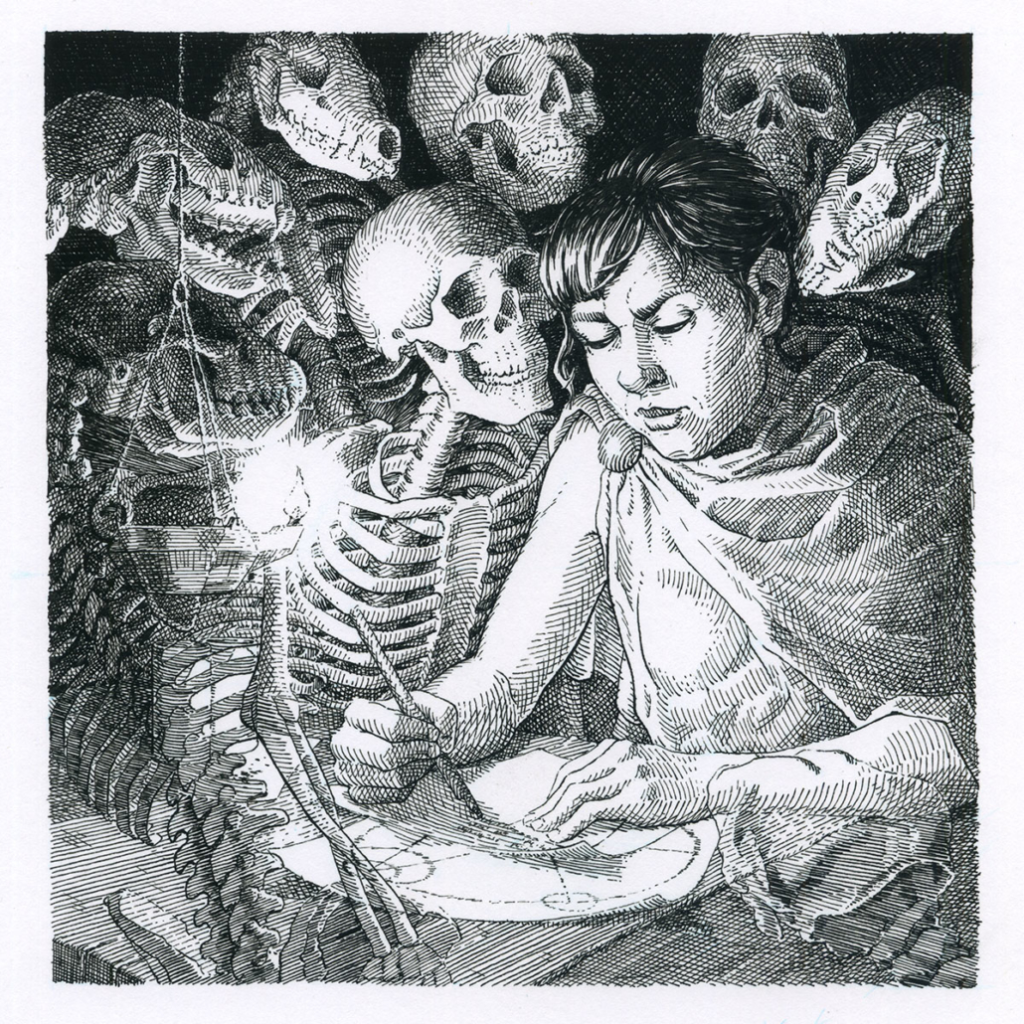

Most of these pieces are from my persnickety pen and ink period — that is, 2019. When 2020 piled on the stress I moved on to more forgiving media.

Witches appear in a lot of my work. As characters who communicate with things beyond the scope of reason, including the spirits of the dead, and as motifs in a long artistic tradition that includes some of my favorite pictures, witches always resonate with me.

I’ve added some etchings, namely a piece that is a reworking or deliberate misreading of the danse macabre motif to be about finding joy in the presence of death.

Where do you make your work?

images of studio

I make my work at home. For many years I lived in Brooklyn, where my studio was also my kitchen, living room, dining room, and guest room. Since moving to the Berkshires I’ve finally had space to set up, among other things, my grandmother’s etching press.

What are your favorite materials to use? Most unusual?

I love India ink and steel-nib dip pens. I sometimes combine this with charcoal tones to achieve an etching-and-aquatint effect for one-off drawings; this is probably my most unusual method, but it isn’t suited to the flat file as the charcoal remains delicate even after fixing. I’ve included a photo.

Actual etching and aquatint is something I’ve begun doing just this year. Acid etching is very procedural and has a sort of alchemistic appeal. Like pen and ink, it’s easy to wreck your whole picture at any time — though it will be the acid, and not a clumsy pen stroke, that does it, and so it’s more about leaving it to fate than furiously concentrating on each mark.

I also started working digitally again recently. Digital is, by contrast, endlessly forgiving, so it’s a nice option to have when things feel overwhelming. Still, unlimited reworkability means it never tells you “step away before you ruin it!” so it’s easy to spend an obscene amount of time on a given piece.

What historical and contemporary artists inspire you?

I seem to return to Goya again and again. His abiding sense of weirdness and the uncanny, as well as his excellent composition — that’s what I aspire to. A lot of his pictures were intended as social commentary, but like those illustrations separated from their text, his symbols and allusions have come unmoored over time, which multiplies their possibilities.

I should mention the golden age illustrators, especially Howard Pyle. The way I go about making a picture is based on their methods.

The contemporary artists I’ve been interested in lately are those whose pictures engage with tradition while also being enlivened by a bold graphic sensibility. Illustrator-turned-painter Rebecca Leveille, the muralist Lauren Ys, and Shangkai Kevin Yu, whose quietly surreal still lifes aren’t half as well known as they should be — to name a few. I’m very attached to pictorial depth, which is at odds with that graphic punch, but I’ve been thinking about ways of bringing them together.

When did you decide you wanted to be an artist?

There are a few answers to that question. Art is in my blood. I’ve been drawing since before I can remember, and some of my earliest memories are about drawing.

But I’ve had a lot of bad art teachers. And I spent years doing graphic design, which seemed like a good way of making art pay the bills, but in fact left little scope for actual creativity.

Then in the span of a few years, my grandmother died, leaving me all her art supplies and equipment; my father died; and I started to develop wrist problems as a result of my full time design job working on the computer. Life is short, the body is frail — I come by my grim themes honestly — and my chance to spend my life doing what I was meant to do (if we are meant to do anything) was slipping away. But then my wife was offered a good job — far away from the city, but with a salary we could both survive on. Thanks to her, I was able to commit to art. I had the time to improve, to develop my skills. No more wasting my time and energy doing almost what I love. I’m very fortunate.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

Anyone who’s interested can view more of my art on Instagram @kitcurry.art or my website, KitCurry.ArtStation.com.