海野恵 Tiffany Megumi Gerdes is one of 12 artists selected as a Gallery 263 2023–2024 Small Works Project artist. This project presents artwork in flat files at the gallery and on our website.Visit Megumi’s Small Works Project page →

Can you tell us a little about yourself?

My name is Tiffany Megumi. I am a visual artist currently based in Massachusetts. I’m originally

from Omaha, Nebraska and Shizuoka, Japan. When I’m not in the studio, I work as a textile

designer, formerly a landscape designer.

What kind of art do you make?

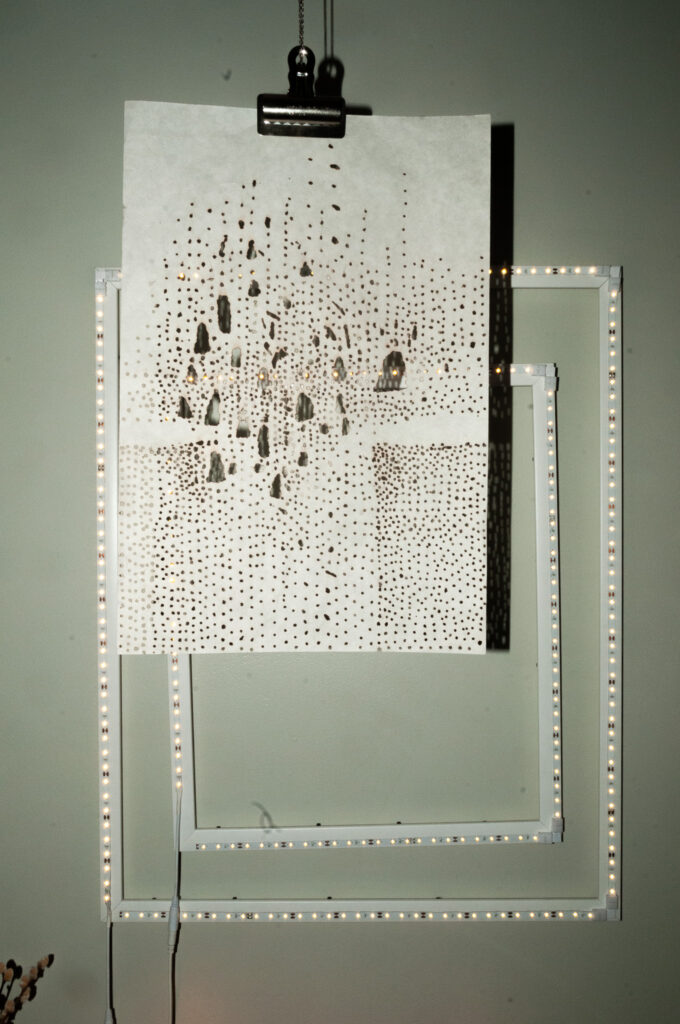

I make drawings I call ‘burn works’ as well as prints and illuminated installations. I am hoping to

dive deeper into papermaking in the next year, a technique I started exploring during lockdown.

What concepts does your art explore?

My work explores stories of interconnectivity and observations within nature and landscapes.

Materially speaking, my work also plays with transience, illusion, and light.

Can you tell us about the work you have on view in your flat file drawer at the gallery?

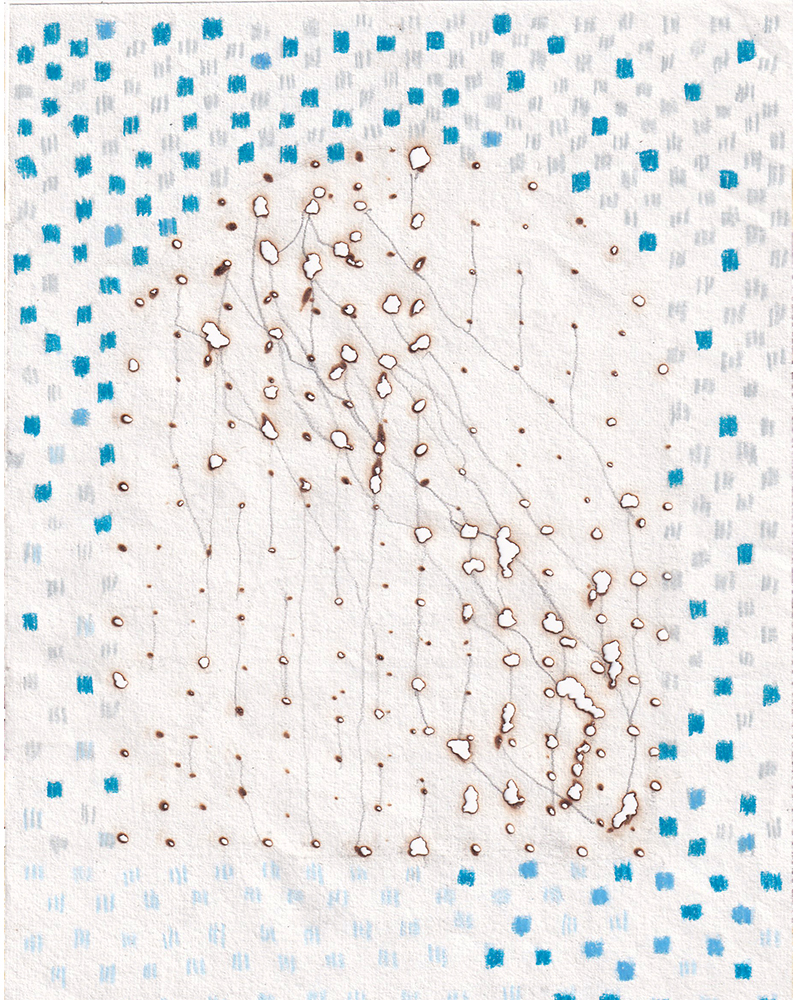

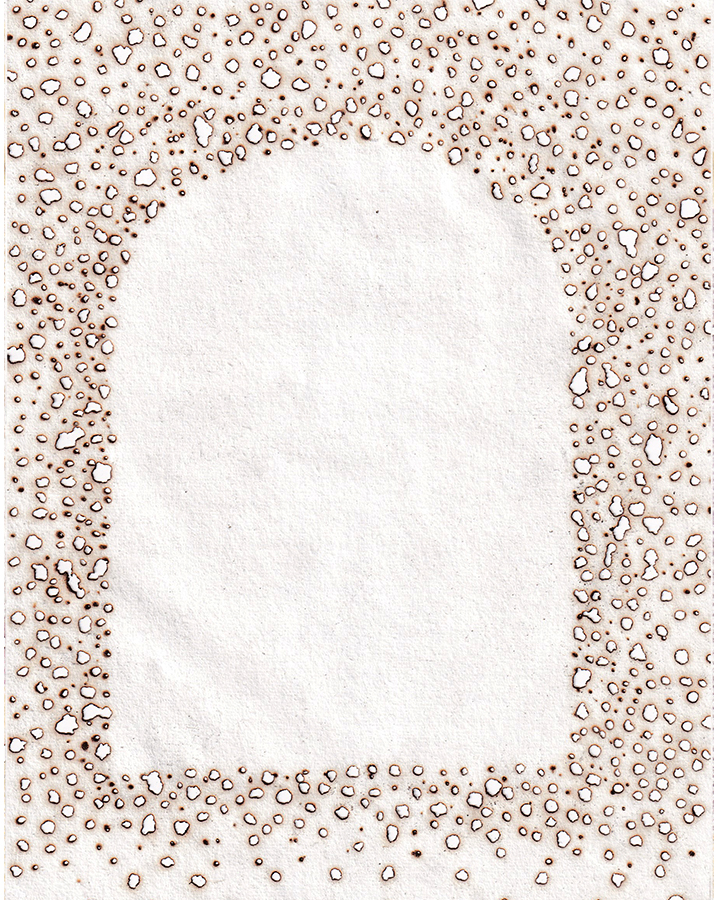

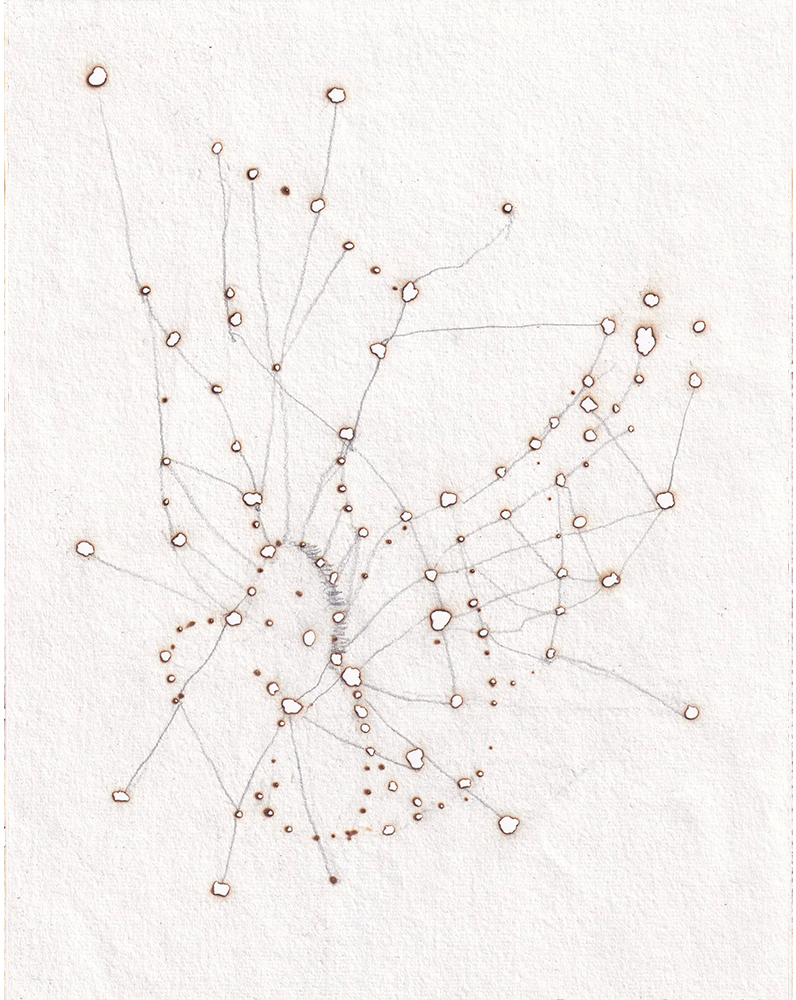

‘Phainesthasia, Objects that Shine Forth’ is a series of drawings that feature illuminated moments

within nature, whether that be the sun setting on an ocean or rain drops accumulating on window

panes. Light and shadow has been a theme particularly in my burn works. I wanted to create a

series of drawings that expanded on this beyond just the material experience.

The title ‘Phainesthasia’ comes from the Greek verb, phao which means ‘to give light, shine,

beam, especially of the heavenly bodies’. The word first appeared in Greek texts like

Aristotle’s ‘De Anima’, where Aristotle attempts to decipher the ‘sparks’ responsible for the

human soul and its truth-seeking desires.

I like the idea of flickering light catching our attention as it forces us to examine our universe

in a more intimate way.

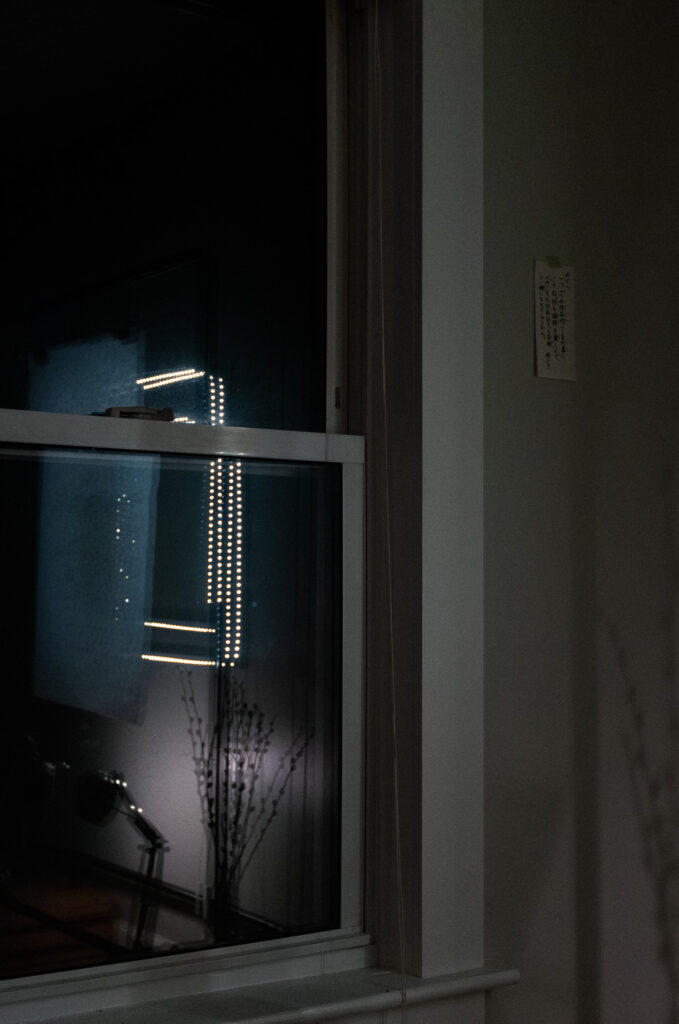

Where do you make your work?

I work out of my in-home studio, usually at night. I like watching the shadows and reflections from

my burn works come alive as they wrap the windows and the walls of my studio. In the past, I

also have worked in community print shops to create pieces like my embossed rice prints.

What are your favorite materials to use?

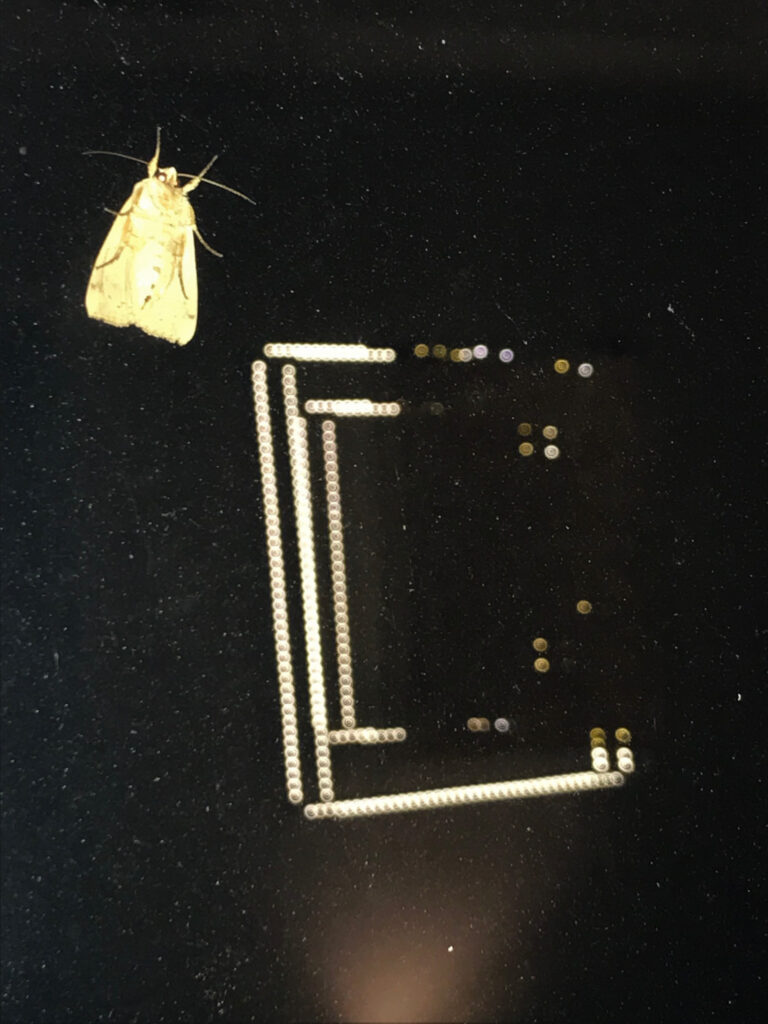

My favorite materials I use are incense and hanshi paper.

Incense I adopted into my work after experiencing Zen Buddhist funerary rituals at my

grandfather’s memorial about 5 years ago. When I first started to make burn works, I treated each

mark as honoring a life cycle or a soul. Burning incense has become an integral part of my

process teaching me to be patient and to surrender to how a piece will unfold.

Hanshi paper is a student grade paper used for practicing calligraphy in Japan. My grandmother

is a Master Calligrapher. I have distinct memories of running past wet hanshi drying on faded

newspapers in the hallway of my grandparents home.

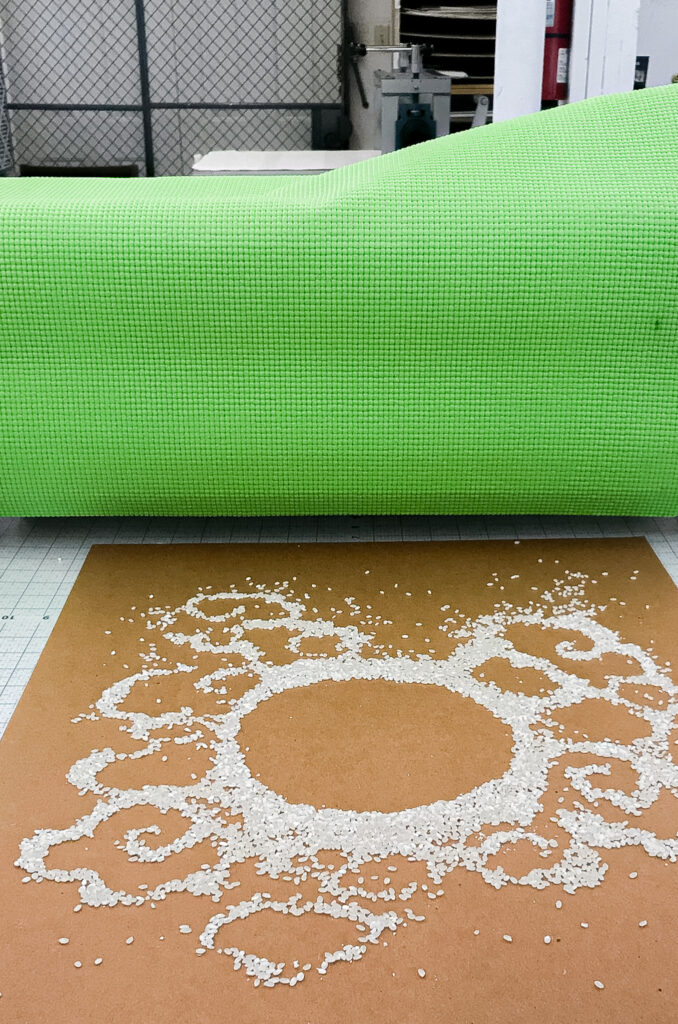

My most unusual material I work with would be rice. I started using rice to create monoprints of

different types of clouds used in Japanese symbolism. Similar to using incense, I like that there is

a lack of control when forming the shapes on the press where the material speaks louder than the

artist.

What historical and contemporary artists inspire you?

I definitely gravitate towards the work of Japanese artists and craftsmen. The nagare

(compositional flow), naive color play and haptic textures have been with me since childhood.

Contemporarily speaking, I enjoy artists who exhibit curiosity and utilize beauty and atmosphere

to bring people together. Olafur Eliasson is one artist I admire that invites wonder and

participation in his work using time and illusions. Leonardo Drew. His commitment to process

and hypnotic textures. Sarah Sze. Her approach to space reminds me of the spirit and rigor I

engaged with while training as a landscape architect. I have many more, but the last one I’ll

mention is my mentor and professor from landscape school, Anu Mathur. She taught me the

power of annotation and metrics when recording fleeting moments within landscapes that I

continue to tap into when creating my work.

When did you decide you wanted to be an artist?

I’ve always avoided it. I steered away from art school hoping it would wane over time. It wasn’t

until I was in my mid-20’s working in the design world that I came to accept my art practice as a

forever thing.

In Shizuoka, I have a lot of early memories of creating in daily life. It was second nature for most

adults and kids I grew up around. My grandfather for example worked as a draftsman in

construction but also had a consistent painting practice he would return to. At school my friends

and I, we’d sculpt sailboats out of styrofoam dango plates so we could race them against the

crayfish in the runnels after school. I’d later come home and there would be a fresh ikebana

arrangement of lilies from my grandparent’s garden in the genkan (entryway). Creativity was

always abundant and considered something everyone had the capacity to nurture.

In the states, I experienced art in a more structured sense. Omaha was an incubator for music

and art when I was coming of age. I had a drawing teacher in middle school who drilled me in

technique. I spent a lot of time obsessing over superrealist precision in portraiture; this was

before I knew what I wanted to evoke in my work. Late high school, early college I interned at the

Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts and met a lot of unique artists-in-residence who opened me

up to the world of abstraction. I think something about living landlocked in the Great Plains

defined a creative energy in me that ultimately chased me to the East Coast.

It’s fascinating how places leave imprints. For me, Japan showed me art as a practice. And

America, art as a persona. Both have been formative in the time it’s taken to embrace my work.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

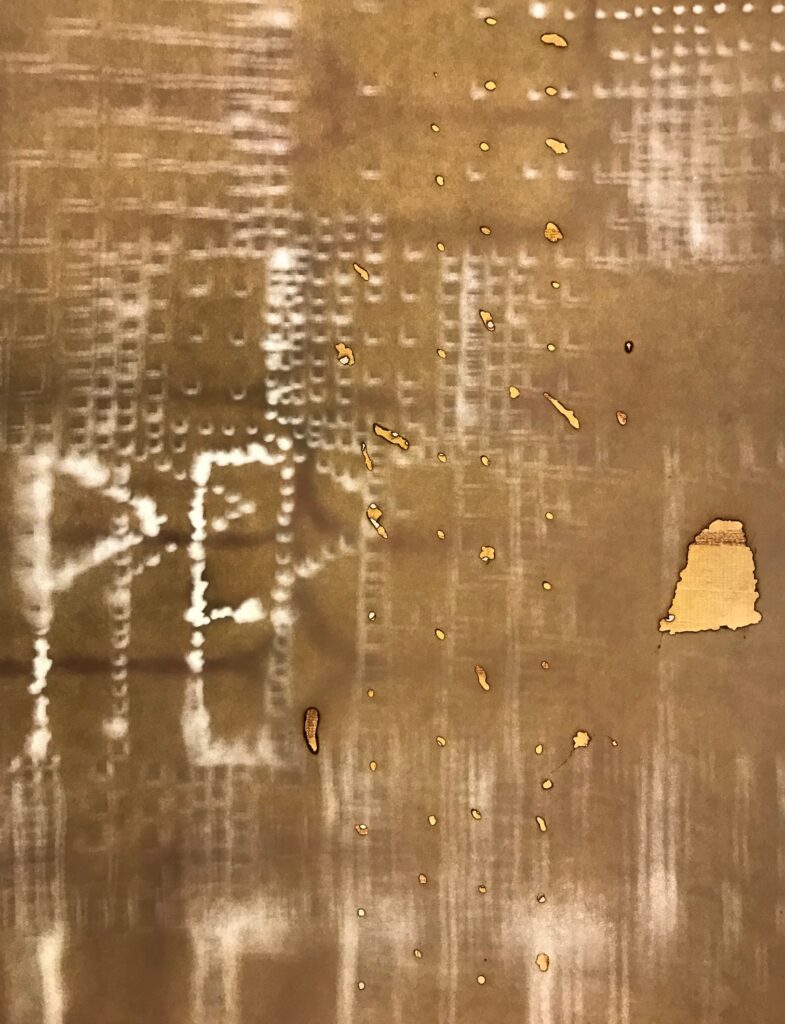

In addition to my small works, I am currently working on a large-scale series of ‘burn works’

inspired by the Japanese dry garden, 枯山水, karensansui. They are works that build off of my

previous large-scale work, ‘Distance is a State of Mind, the Mandala Series’. My goal for this

work has been to deepen my drawing language by introducing folkloric elements hidden within

these gardens but also to explore the sacred geometries used in karensansui. The dry garden

specifically is an exercise in world-making from creating mountains out of the energetic

placement of rocks to recreating the flow of water using raked gravel formations. I’m interested in

how these forms ultimately come together to create a transcendent landscape, one that lives

within the mind.