During the COVID-19 pandemic, we interviewed a handful of former Gallery 263 exhibiting artists to see if and how their practice was evolving due to the pandemic.

Tell us about yourself and your practice.

I am a visual artist and educator living in Malden with my husband and three small children. Since 2014, I have been teaching in the College of Fine Arts at Boston University and in my practice, I work mainly with photography and photographic materials. One of my earliest experiences with photography happened when I was six years old. I stole my mother’s point and shoot Vivitar camera from the kitchen drawer and used up the rest of the roll photographing my friend running around the yard. I then slipped the camera back into the drawer thinking I’d never be caught. The film was eventually processed and my mother was not too happy. Film was precious, saved for birthdays or the first day of school. Nevertheless, she let me keep the prints. I wouldn’t return to photography until sophomore year of college. While studying literature, I took an elective in the darkroom and I knew I had found my place. The magic of the darkroom had a profound impact on me, I was reminded of that sense of freedom in the yard with the Vivitar camera in hand, chasing the light.

In my practice, I am primarily interested in photography both as a medium and, more broadly, as a way of seeing. How do photographs shape how we communicate, remember, and experience the world and what we value? Also, how, as an artist, can I push the medium beyond its indexical nature? The poet Paul Valéry wrote, “To see is to forget the name of the thing one sees.” I enjoy finding the possibilities and limitations of photography – how it can make us both remember and forget, make something feel entirely present and absent, and show us something beyond the frame. I view the medium of photography as a tool amongst many that I use in the studio. Occasionally, the camera is the answer to my creative question. But, oftentimes, I am using other techniques including mold-making, assemblage, embroidery, performance, and laser etching. Again, as I weave these varied processes into my practice, my focus is always turned toward how these materials relate to photography in an expanded sense.

How has your creative practice shifted and adapted during the pandemic?

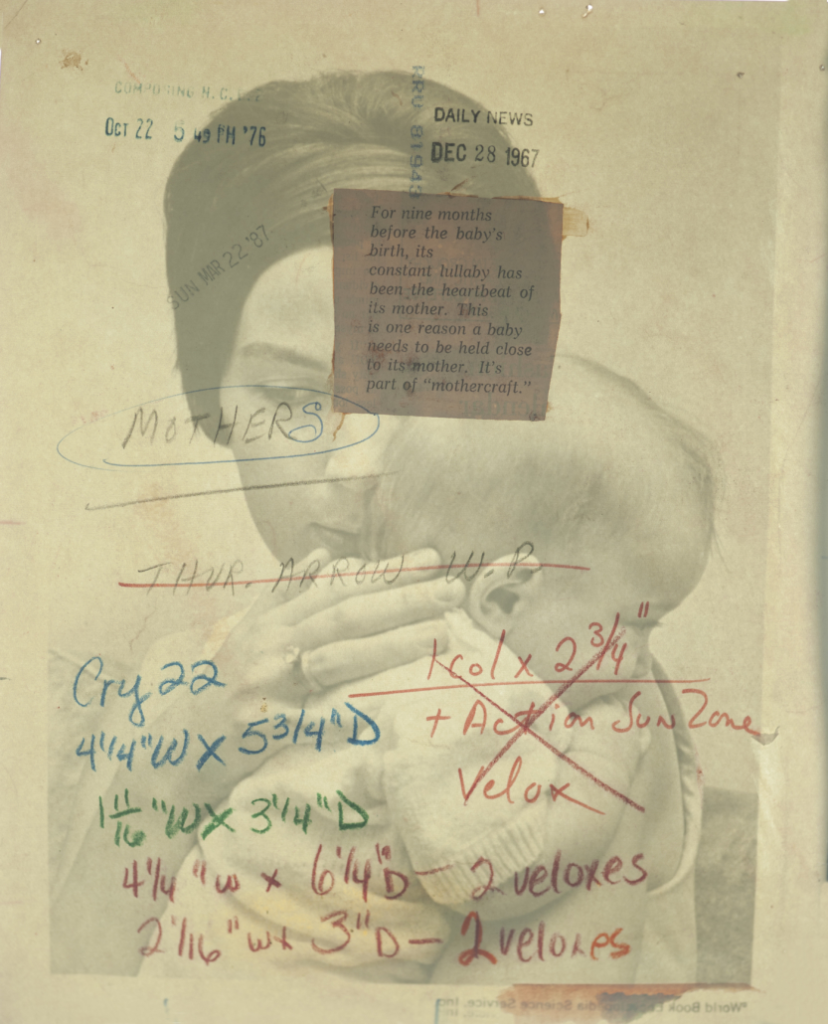

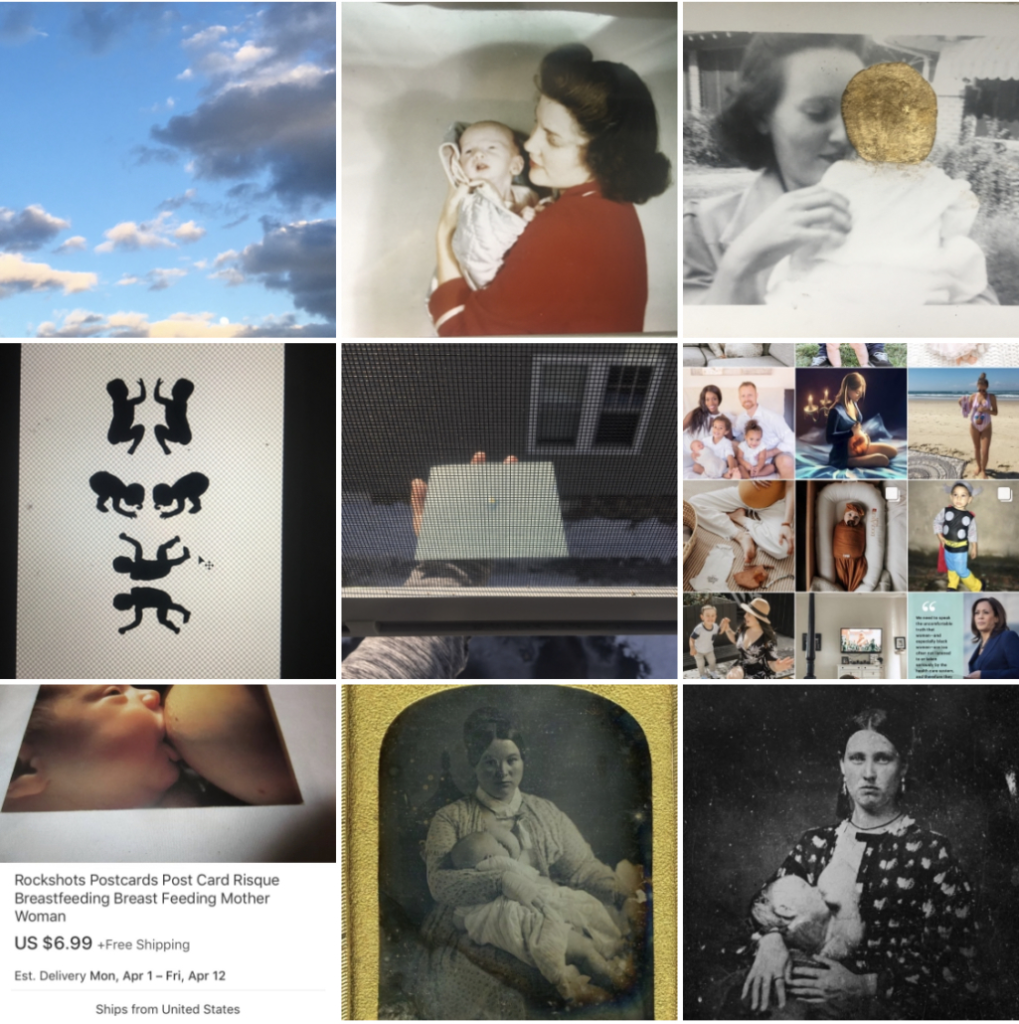

images of work

My sense of time completely shifted during the pandemic. This also happened when I became a mother. So much of early parenting is tied to the clock with regimented nap, feeding, and sleep schedules. During the early months of the pandemic, however, it was as if we dismantled the clock and made time our own. Each hour’s purpose dissolved and this gave me room to observe my home and surroundings in a way that I haven’t been able to. I also could not compartmentalize my life into work time, family time, studio time – it all melted together. This was often problematic, as it was difficult to focus, but it also allowed me to see how these worlds can come together in a more meaningful way. After two gray months, I began a garden with my children, growing seedlings in our kitchen. This led to a summer of photographs in the garden, and research about plants and mythology. My practice also became tied to a different clock, the sun and the seasons. In order to photograph the garden, I had to wait for growth or, in the later months, hurry to capture something before the first frost. Prior to the lockdown, my images were all staged, lit entirely by strobe lights and photographed over and over again until I found the right moment. With the garden, however, once it was over, it was over. There was no returning to a moment, at least not until next spring.

How has the content of or approach to your work shifted because of current events?

I’ve been exploring the idea of mothers as givers of life and death in my own work for several years now. This notion comes from the writer Samantha Hunt, who upends the sentimental versions of motherhood by integrating the sobering idea of death. There are many ways in which birth and death intertwine. They are events that should exist on opposite ends of a pole, but echo a certain kind of commonality in their mystery and significance. In becoming a mother, I had to face my own mortality and my children’s in ways I never did before. I became much more aware of the razor thin line between life and death and that the joys of parenting are not exempt from this encroaching darkness. Throughout the pandemic, I have been confounded by the fact that there is so much loss and grief surrounding us without any collective visual representations to inculcate the magnitude of this moment. The absence of these images is not surprising; our society tends to sterilize and make invisible the messiness of death, just as we do with birth. During this time, I’ve become more interested in visualizing our rituals and sites for death. Since the summer, I’ve been collecting and photographing found snapshots of graveside visits, with floral arrangements that spill onto the ground wrapped in limp ribbons and held in place by foam and plastic vessels. The back of one photograph reveals a handwritten note, “Aren’t the flowers pretty?” it reads. This comment along with the conventional framing, expressions, and poses found throughout the collection illustrate an impulse to maintain our attention on life even when trying to capture death. If death is something we typically want out of sight, what is it to bring it into focus? The pandemic has certainly encouraged me to pursue this question in a way I would not have prior.

Do you have plans to transform your work or approach in 2021?

I have plans for a solo exhibition at the Danforth Art Museum in the Fall of 2022, which was delayed due to the pandemic. The body of work in progress for this exhibit is entitled An Ordinary Devotion, which is a reference to an excerpt from Maggie Nelson’s Argonauts:

“The pleasure of abiding. The pleasure of insistence, of persistence. The pleasure of obligation, the pleasure of dependency. The pleasures of ordinary devotion. The pleasure of recognizing that one may have to undergo the same realizations, write the same notes in the margin, return to the same themes in one’s work, relearn the same emotional truths, write the same book over and over again—not because one is stupid or obstinate or incapable of change, but because such revisitations constitute a life.”

So much of my practice transformed early on in the pandemic and I want to continue to pursue those methods. I have enjoyed working more spontaneously and incorporating time into my process in a way that creates parameters for when and where I can make an image. I look forward to getting back outside in the warmer months and revisiting the garden. I also have several in-progress pieces that integrate image and sculpture/dimension in ways that are new to me. The inability to see artwork in person for much of this past year has made me consider presentation and the in-person vs. screen experience of viewing. How can an image reference the physical space it is pointing back toward in a more tangible way? I want this new work to incorporate the viewer’s body, to direct their movement and line of sight so as to bring together the photographic space of the image with the viewing space of the audience.